Jaime de Angulo came to the coast — on horseback — in 1915. No one's written of the sheer dizzying wildness of this coast like he has. Later in his life he wrote an account of his first experience with the coast — an account which remained untitled among his unpublished papers when he died.

But it's been published since, first under the title "La Costa del Sur" in A Jaime de Angulo Reader, and more recently as "First Seeing the Coast" in The Lariat and Other Writings.

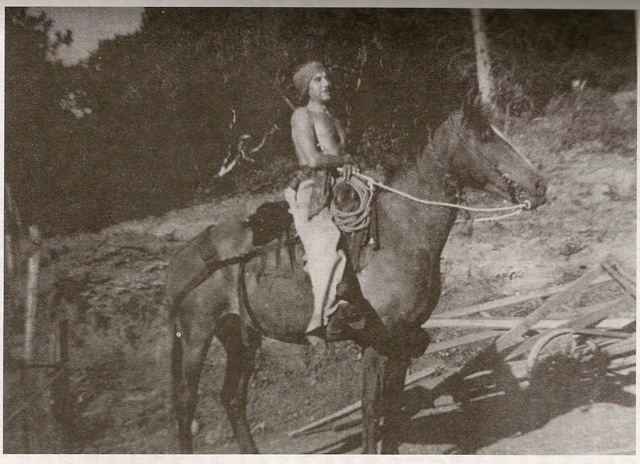

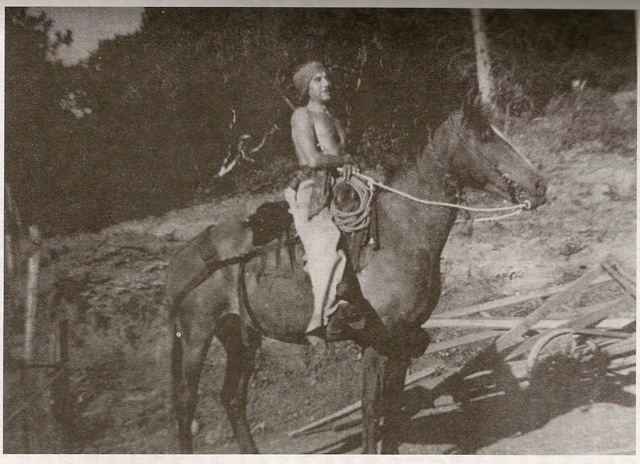

Jaime de Angulo on HudiniJaime was away from the coast for seventeen months in the early 1920's when he was doing linguistic work in Mexico — and when he returned in the winter of 1923, he was shocked to discover the highway being built.

Jaime de Angulo on HudiniJaime was away from the coast for seventeen months in the early 1920's when he was doing linguistic work in Mexico — and when he returned in the winter of 1923, he was shocked to discover the highway being built.

Courtesy of the Ewoldsen family. Photo appears in "Big Sur" by Jeff Norman and the Big Sur Historical Society.The following are excerpts from a letter he wrote to his first wife, Cary Fink, on December 14, 1923.

Courtesy of the Ewoldsen family. Photo appears in "Big Sur" by Jeff Norman and the Big Sur Historical Society.The following are excerpts from a letter he wrote to his first wife, Cary Fink, on December 14, 1923.

"Meanwhile you can picture to yourself the fever on the Coast. People rushing down to buy land as if to a Klondike. All land gone sky high. Partington Cañon is sold to those people Chauncey wrote about, who formed a 'Trail Club' (and had started buying a piece near Post). But they are not at all a gun club, but people from Carmel, mostly, among them Mrs. Porter of the deep voice, who have formed a trust company and bought it to 'preserve the redwoods'...

"We had great fun out of them. They went away round eyed, ho-in and ha-in and talking 'building sites.' Rather nice people on the whole — and certainly infinitely better than a 'gun club' which is what I feared.

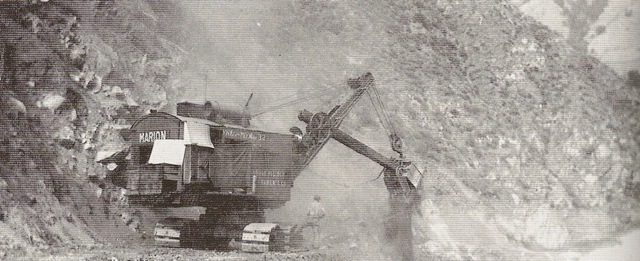

"But my coast is gone, you see. It will be an altogether different affair. I don't know what to think of it, on the whole. My first reaction of course was one of intense sorrow and horror. My Coast had been defiled and raped. The spirits would depart. And as I travelled with Mr. Farmer (the stage man) past Castro's place, past Grimes' cañon, and contemplated the fearful gashes cut into the mountain, and the dirt sliding down, right down into the water in avalanches, my heart bled."

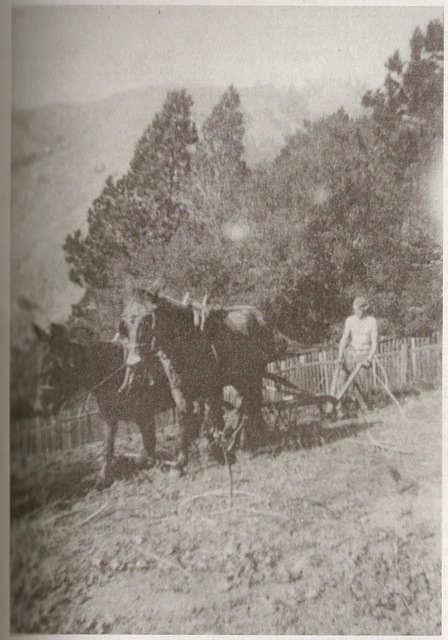

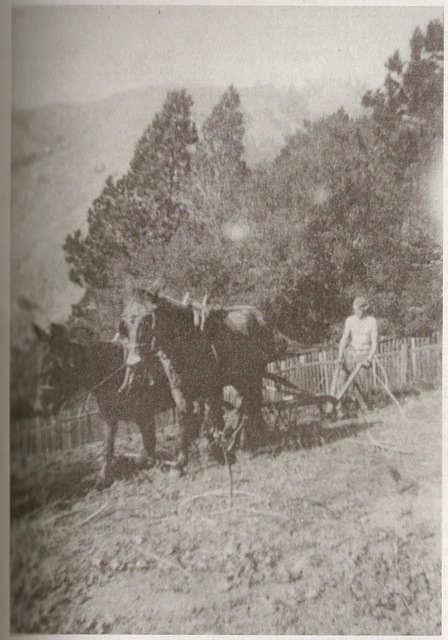

Jaime plowing at Los PesaresYears later, when Jaime wrote his account of coming to the coast, he described El Mocho — Roche Castro — leading him straight up a mountainside so steep that as skillful a horseman as Jaime was..."I must confess I got dizzy and had to get off my horse and lead him, much to the Mocho's amusement."

Jaime plowing at Los PesaresYears later, when Jaime wrote his account of coming to the coast, he described El Mocho — Roche Castro — leading him straight up a mountainside so steep that as skillful a horseman as Jaime was..."I must confess I got dizzy and had to get off my horse and lead him, much to the Mocho's amusement."

Roche was leading Jaime to a hillside sixteen hundred feet above the ocean, where Jaime would homestead the ranch he called "Los Pesares."

"What a scene! Yes, I lost my heart to it, right there and then. This is the place for a freedom loving anarchist. There will never be a road into this wilderness...it's impossible! Alas, nothing is impossible to modern man and his infernal progress: they came with bulldozers and tractors before very long, and raped the virgin. Roads and automobiles, greasy lunch-papers and beer-cans, and their masters. And the shy Masters of the Wilderness receded to the depths of the canyadas, and back over the Ridge, into the yet unraped country of the Forest Reserve — but even there they are not safe..."

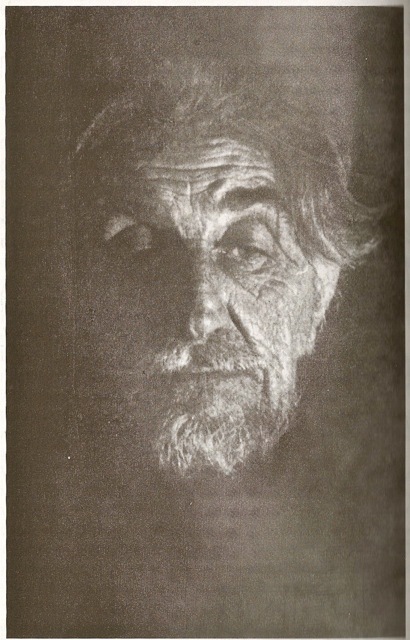

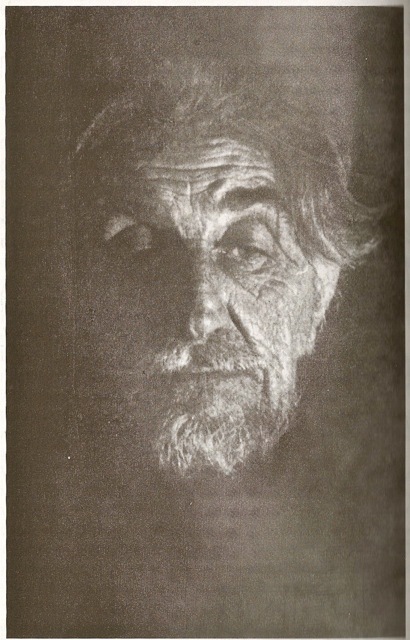

The "old coyote of Big Sur" in 1948I don't know what you make of these "shy Masters of the Wilderness," these spirits whom Jaime said would flee the building of the highway — but I take them seriously.

The "old coyote of Big Sur" in 1948I don't know what you make of these "shy Masters of the Wilderness," these spirits whom Jaime said would flee the building of the highway — but I take them seriously.

And there's no bigger question for this coast than what will become of them.

_______________________________

Notes

The three photos of Jaime de Angulo appear courtesy of Gui de Angulo's biography of her father, The Old Coyote of Big Sur: the Life of Jaime de Angulo.

The Old Coyote of Big Sur: the Life of Jaime de Angulo is available on-line and in person at The Henry Miller Library in Big Sur.

Thursday, April 21, 2011 at 10:17AM

Thursday, April 21, 2011 at 10:17AM

Ts'owém' (Cone Peak). John Peabody Harrington, October 1932. Courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives. _____________________________

Ts'owém' (Cone Peak). John Peabody Harrington, October 1932. Courtesy of the National Anthropological Archives. _____________________________ Cone Peak,

Cone Peak,  John Peabody Harrington,

John Peabody Harrington,  Tsowem in

Tsowem in  The Coast-Road

The Coast-Road