“Uncle Mehmet isn’t here…”

Saturday, March 28, 2009 at 3:04PM

Saturday, March 28, 2009 at 3:04PM  You look at any one of these earth-forms

You look at any one of these earth-forms

…and they could be peopled still.

…and they could be peopled still.

The soft tufa – volcanic ash mixed with sandstone – makes it possible.

The soft tufa – volcanic ash mixed with sandstone – makes it possible.

In Cappadocia, early Christians carved vast underground cities out of it -- where they could hide for months at a time from Roman soldiers.

In Cappadocia, early Christians carved vast underground cities out of it -- where they could hide for months at a time from Roman soldiers.

Centuries later, they hid again from Arab invaders.

Here at Keşlik Manestir the tufa mounds seem both to congregate and to be on the move at once, as if each of them still has something it wants to say,

Here at Keşlik Manestir the tufa mounds seem both to congregate and to be on the move at once, as if each of them still has something it wants to say,

…which may be true since manestir means monastery in Turkish. And Keşlik is thought to be one of the oldest monasteries in Cappadocia, which means it was one of the oldest monasteries anywhere.

…which may be true since manestir means monastery in Turkish. And Keşlik is thought to be one of the oldest monasteries in Cappadocia, which means it was one of the oldest monasteries anywhere.

Each apparently blank form could be…

Each apparently blank form could be…

…through one story after another of good earth

…through one story after another of good earth

…until perhaps it disappears entirely underground

…until perhaps it disappears entirely underground

…only to connect with all the others in ways we can no longer perceive.

…only to connect with all the others in ways we can no longer perceive.

And you begin to suspect that there’s no end to the subterranean passageways that connect all of us in some vast lost time we don’t understand either.

And you begin to suspect that there’s no end to the subterranean passageways that connect all of us in some vast lost time we don’t understand either.

Sometimes the signs are virtually effaced, and human art melds easily back into earth’s forms and colors again.

Sometimes the signs are virtually effaced, and human art melds easily back into earth’s forms and colors again.

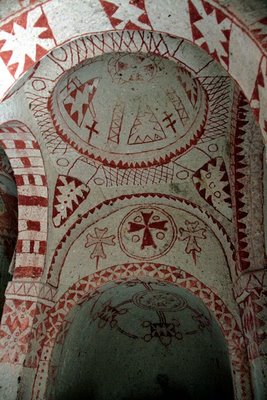

Sometimes a human hand has painted a chapel with wild and archaic forms.

Sometimes a human hand has painted a chapel with wild and archaic forms.

And sometimes it seems as if the Byzantine fresco painter just walked out yesterday and left the pigments to dry on the wall behind him.

And sometimes it seems as if the Byzantine fresco painter just walked out yesterday and left the pigments to dry on the wall behind him.

The landscape helps decide what should be preserved – and for how long and in what form.

The landscape helps decide what should be preserved – and for how long and in what form.

But it is also true that Turkey’s population is approximately 98% Muslim now,

…and there hasn’t been a Byzantine monk living in any of these caves in more than 700 years.

…and there hasn’t been a Byzantine monk living in any of these caves in more than 700 years.

And yet their presence is still so strong that our friend Torrey says he became a Christian because of them.

And yet their presence is still so strong that our friend Torrey says he became a Christian because of them.

So what else should we do, but look for these monks ourselves?

We stopped to ask a farmer for directions to Pancarlik Manestir. He wouldn’t tell us.

We stopped to ask a farmer for directions to Pancarlik Manestir. He wouldn’t tell us.

Instead, he packed up the dried apricots and mulberries in the back of his truck and came to show us.

This kept happening. At each turn we’d make a new friend, like Pinar in Göreme

This kept happening. At each turn we’d make a new friend, like Pinar in Göreme

…and Unal who drove us to the most hidden monasteries he knew.

…and Unal who drove us to the most hidden monasteries he knew.

Angels would make themselves visible on city streets if that’s what it took to show us where to go next.

Angels would make themselves visible on city streets if that’s what it took to show us where to go next.

But when we had arrived at Pancarlik Manestir, there was no one to open the chapel for us. It wasn’t yet the season for visitors.

But when we had arrived at Pancarlik Manestir, there was no one to open the chapel for us. It wasn’t yet the season for visitors.

…and there were flowers and candles on the altar inside.

…and there were flowers and candles on the altar inside.

So each of us wandered off on our own to imagine a community of monks and caves and stone. It was easy to do since the place was so well kept.

So each of us wandered off on our own to imagine a community of monks and caves and stone. It was easy to do since the place was so well kept.

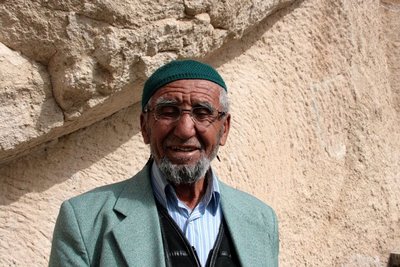

We met a guide walking along the sandy road.

We met a guide walking along the sandy road.

“Who’s the man who keeps care of the monastery?” I asked.

“Oh, that’s Uncle Mehmet…”

“He must be a good man.”

“He’s a very good man,” the guide said. “I’m going now to buy some tea and sugar to give to him. He always makes tea for his visitors.”

“He’s a very good man,” the guide said. “I’m going now to buy some tea and sugar to give to him. He always makes tea for his visitors.”

“Would you buy Mehmet some tea for us?” we asked.

“Of course.” From Cappadocia, we made a long bus ride to Konya, the home of Rumi.

From Cappadocia, we made a long bus ride to Konya, the home of Rumi.

The woman in front of us was reading the Qur'an.

She was also reading perfect English.

She was also reading perfect English.

Konya is a big and conservative city. Hülya took us by the hand, led us from the bus to tram, bought our tickets, and took us downtown.

Konya is a big and conservative city. Hülya took us by the hand, led us from the bus to tram, bought our tickets, and took us downtown.

We went to her mosque, where she prayed, and we did, too. Then she walked us to our hotel and gave us her phone number and asked us to call her if we needed anything.

We went to her mosque, where she prayed, and we did, too. Then she walked us to our hotel and gave us her phone number and asked us to call her if we needed anything.

It’s true that we couldn’t find a beer or glass of wine in Konya.

It’s true that we couldn’t find a beer or glass of wine in Konya.

It’s also true that each person we met was kind and generous with us.

Conservative, we learned again, isn’t a synonym for extremist or fundamentalist. In Konya, it seems to mean something closer to faithful instead.

Conservative, we learned again, isn’t a synonym for extremist or fundamentalist. In Konya, it seems to mean something closer to faithful instead.

But we couldn’t find Rumi either -- moved as we were to pay our respects at his tomb.

But we couldn’t find Rumi either -- moved as we were to pay our respects at his tomb.

“You won’t find me here,” he said.

“What dome could you build for me that would be better than the open sky?”

“What dome could you build for me that would be better than the open sky?”

“My grave will be in the hearts of the wise.”

“My grave will be in the hearts of the wise.”

His Friend, Shams of Tabriz, went even further.

“I will go somewhere where words will never find me,” Shams said.

When we visited Shams’ turban...

When we visited Shams’ turban...

...a couple of people were praying quietly in the small mosque.

...a couple of people were praying quietly in the small mosque.

But as we started to leave, four men were coming in. The man who takes care of the mosque smiled and nudged us back inside. And just then, one clear voice rose into the air in a long beautiful stream of praise and poetry and prayer and song.

The voice must have spilled outside because soon women began following it inside and crooning in a low undertone of prayer themselves.

The voice must have spilled outside because soon women began following it inside and crooning in a low undertone of prayer themselves.

The Sufis are here, the Sufis are here! they must have been saying.

Afterwards the Sufis told us, “We aren’t from here,” as they gestured to the city streets all around us. “Do you understand?”

Afterwards the Sufis told us, “We aren’t from here,” as they gestured to the city streets all around us. “Do you understand?”

They were from Bosnia. But that’s not what they meant. They meant they weren’t from this realm of commotion and inner noise.

They wanted us to come with them to their "Sufi place" at Menzil.

They wanted us to come with them to their "Sufi place" at Menzil.

“We want to push you into the ocean,” they said.

But we had a bus to catch. You can’t say yes to everything.

So we bowed and shook hands and touched our hearts and went our separate ways.

So we bowed and shook hands and touched our hearts and went our separate ways.

"We'll fall into the ocean anyway," we said.

Later, on our plane back to Istanbul, we were sitting among a group of thirty, mostly women, buzzing with excitement at beginning their pilgrimage to Mecca.

Later, on our plane back to Istanbul, we were sitting among a group of thirty, mostly women, buzzing with excitement at beginning their pilgrimage to Mecca.

We laughed and gestured and touched our hearts many times with them, too.

“We’ll pray for you,” they said. “Please pray for us, too.”

“We’ll pray for you,” they said. “Please pray for us, too.”

They had already given each of us their prayer beads.

In Cappadocia the 4c was the century of three saints: St. Basil the Great, his brother St. Gregory of Nyssa, and their friend, St. Gregory of Naziaranus.

In Cappadocia the 4c was the century of three saints: St. Basil the Great, his brother St. Gregory of Nyssa, and their friend, St. Gregory of Naziaranus.

Had we met Uncle Mehmet, he probably wouldn’t have parsed their mystical theology for us.

Cappadocia,

Cappadocia,  Konya,

Konya,  Rumi | in

Rumi | in  Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage