The God-trodden mountain – Sinai

Sunday, May 3, 2009 at 12:22AM

Sunday, May 3, 2009 at 12:22AM  Some places feel like dreams now,

Some places feel like dreams now,

…both faintly written, as day turns into day,

…both faintly written, as day turns into day,

…but also with a haunting vividness should one have the courage to summon up the images again.

…but also with a haunting vividness should one have the courage to summon up the images again.

Perhaps that’s one reason for our reluctance to glance backwards

Perhaps that’s one reason for our reluctance to glance backwards

…because there are beauties and questions that linger on, and which at any moment can break your heart again,

…because there are beauties and questions that linger on, and which at any moment can break your heart again,

…and who is so eager to open that Pandora’s box?

…and who is so eager to open that Pandora’s box?

But, of course, dream-images are also gifts.

But, of course, dream-images are also gifts.

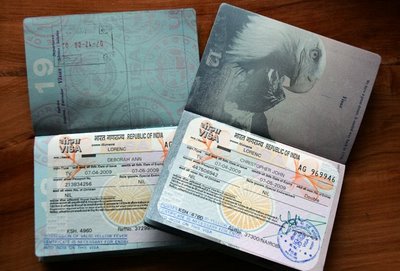

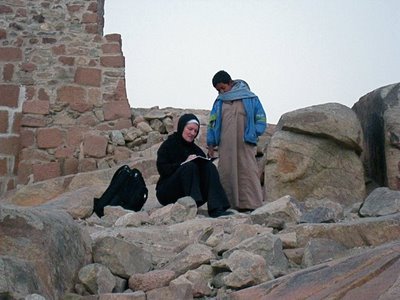

(You didn’t know that Debi was thinking of becoming a nun, did you?)

She’s just not quite certain to which order she’ll belong.

She’s just not quite certain to which order she’ll belong.

As long as she has been writing icons,

As long as she has been writing icons,

…in fact, perhaps as long as she’s known what an icon really is,

…in fact, perhaps as long as she’s known what an icon really is,

…at the foot of the God-trodden mountain,

…at the foot of the God-trodden mountain,

…Mount Sinai.

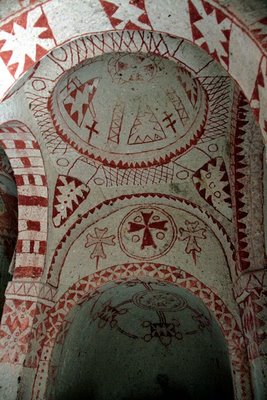

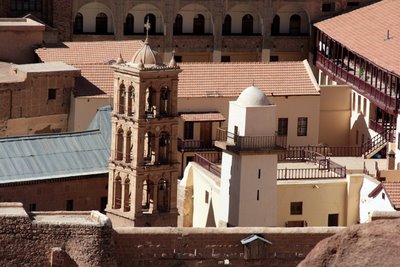

It is the oldest continuously existing Christian monastery in the world,

It is the oldest continuously existing Christian monastery in the world,

…built upon the site of the Burning Bush.

…built upon the site of the Burning Bush.

It is also the only Christian monastery in the world to have a mosque within its walls.

It is also the only Christian monastery in the world to have a mosque within its walls.

![]() God might not be descending quite so dramatically right now.

God might not be descending quite so dramatically right now.

Still, you might want to take your sandals off. Isn’t everywhere holy ground?

Still, you might want to take your sandals off. Isn’t everywhere holy ground?

Sometimes it must sound like only rhetoric – the way we speak to you in the second person

Sometimes it must sound like only rhetoric – the way we speak to you in the second person

This is Judy Delany. She and Debi have known each other for forty years -- and in addition to her friendship with both of us and emails brimming with energy and support, she makes comments here as "Schweetiecakes."

Notice her "Red Egg" necklace.

Since our last blog, many of you have sent generous notes and new ideas.

Since our last blog, many of you have sent generous notes and new ideas.

Sometimes your ideas seem like they’re arising at the same time as our own, and sometimes, like with Peggy, it seems you’re half a step ahead of us.

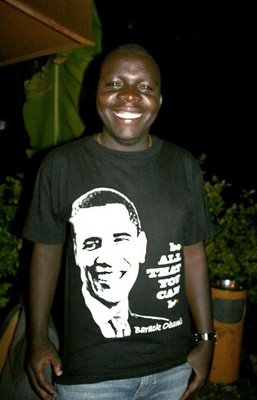

Here is Peggy O'Farrell two years ago in the Philippines.

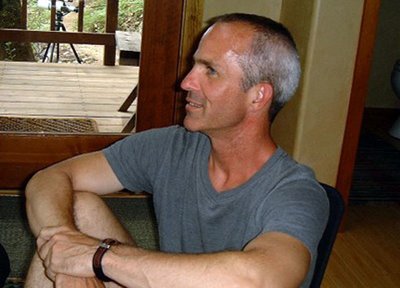

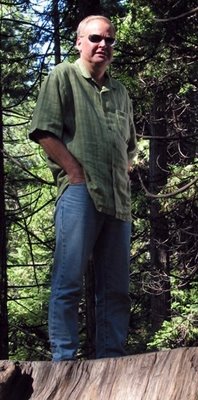

Dennis Gobets has been keeping the home-fires burning – and doing his own gallivanting, too.

Dennis Gobets has been keeping the home-fires burning – and doing his own gallivanting, too.

He's been helping keep an eye on Rocky Creek and

...inviting us to go with him to the southwest when we return.

...inviting us to go with him to the southwest when we return.

So while we’ve been at our crossroads, he’s been contemplating his own descent into a canyon.

Steve Tryon has been with us from the beginning, every step along the way. Without him, the Red Egg website and these words and images wouldn’t be appearing – or not the way they do.

Steve Tryon has been with us from the beginning, every step along the way. Without him, the Red Egg website and these words and images wouldn’t be appearing – or not the way they do.

He writes, “I think you are in the perfect position…”

…and offers to help even more what he calls the beginning of “a yours-become-ours journey through mind, matter, and connectedness.”

Shall we say that again?

It has become a new mantra for us.

It has become a new mantra for us.

Or better yet, can we keep saying it to one another – because we are saying it to you just as so many of you have been saying that to us.

Or better yet, can we keep saying it to one another – because we are saying it to you just as so many of you have been saying that to us.

This is Debi’s neo-Coptic icon teacher Stephane Rene and his wife Monica – when we were with them in London.

We had assumed that crossroads meant: that either we’d come home earlier than we had thought, or we’d travel on awhile more.

We had assumed that crossroads meant: that either we’d come home earlier than we had thought, or we’d travel on awhile more.

But what if you’ve been teaching us

But what if you’ve been teaching us

…that somehow it’s possible to do both things at once?

…that somehow it’s possible to do both things at once?

But enough of that for now. We still have a mountain to ascend.

But enough of that for now. We still have a mountain to ascend.

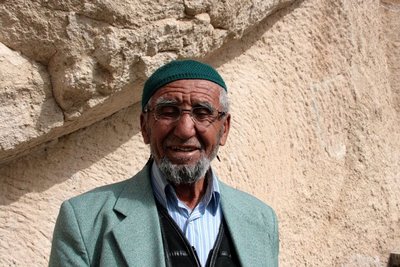

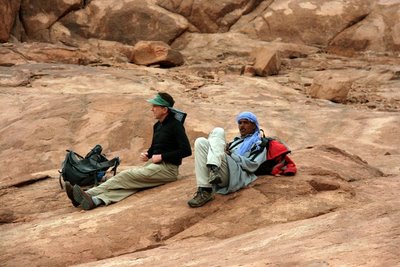

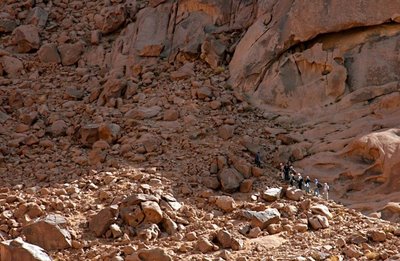

Our Bedouin guide Nasr understood at once and had chosen the least-traveled path to the mountain.

Our Bedouin guide Nasr understood at once and had chosen the least-traveled path to the mountain.

In fact, sometimes it appeared to be no way at all.

In fact, sometimes it appeared to be no way at all.

But hasn't that been the point all along?

This has never been a tourist-trip

…even if sometimes it might appear that way.

…even if sometimes it might appear that way.

After a few hours, Nasr led us up a draw where he knew rainwater would be pooled.

After a few hours, Nasr led us up a draw where he knew rainwater would be pooled.

We gathered brushwood for a fire there.

We gathered brushwood for a fire there.

Debi and I have backpacked and hiked a lot -- but we have never had a hiking-lunch like this.

Debi and I have backpacked and hiked a lot -- but we have never had a hiking-lunch like this.

Nasr kneaded and rolled wheat-flour and water on the stone

The bread went right into it – because in the Sinai, if you’ve gotten the sand hot enough

The bread went right into it – because in the Sinai, if you’ve gotten the sand hot enough

…it will not stick to even bread.

…it will not stick to even bread.

He roasted eggplant for the baba ganoush – and cut peppers and tomatoes and lemons,

He roasted eggplant for the baba ganoush – and cut peppers and tomatoes and lemons,

…while Debi helped with the garlic.

…while Debi helped with the garlic.

Nasr always brings black tea with him,

Nasr always brings black tea with him,

…but he also gathers herbs to add to it.

…but he also gathers herbs to add to it.

His tobacco is from the desert, too. He knows all of Sinai’s plants

His tobacco is from the desert, too. He knows all of Sinai’s plants

...and Sinai is the most bio-diverse place in Egypt.

...and Sinai is the most bio-diverse place in Egypt.

Nasr gathered more plants after lunch

Nasr gathered more plants after lunch

“Food always tastes better in the mountains,” I said afterwards.

“Food always tastes better in the mountains,” I said afterwards.

“Everything is better in the mountains,” Nasr says.

We did pass a few other pilgrims along the way, it is true,

We did pass a few other pilgrims along the way, it is true,

…but they were all occupied more or less as we were.

Two days later I went up the mountain on my own. It wanted to take the Sikket Saydna Musa, the steepest route, the one tradition says Moses had taken himself when he climbed alone to meet the one who had told him here, I AM.

Two days later I went up the mountain on my own. It wanted to take the Sikket Saydna Musa, the steepest route, the one tradition says Moses had taken himself when he climbed alone to meet the one who had told him here, I AM.

Byzantine monks laid down the stones of this path fourteen hundred years ago.

Byzantine monks laid down the stones of this path fourteen hundred years ago.

Why have stones been so prominent all along our way?

Why have stones been so prominent all along our way?

Stones and sin. Gathering them sometimes

Stones and sin. Gathering them sometimes

…and at other times casting them away.

…and at other times casting them away.

Remember Iona then?

The Sikket Saydna Musa is also sometimes called the “Stairway of Repentance,” or the “Stairway of Forgiveness.”

The Sikket Saydna Musa is also sometimes called the “Stairway of Repentance,” or the “Stairway of Forgiveness.”

There is a repentance gate as well that you must pass through,

…and both before and after this gate, pilgrims have built cairns everywhere.

…and both before and after this gate, pilgrims have built cairns everywhere.

How can you not be mindful passing through a repentance gate, especially since beyond it Elijah stayed, and that beyond even that, Moses still climbed?

How can you not be mindful passing through a repentance gate, especially since beyond it Elijah stayed, and that beyond even that, Moses still climbed?

(Please excuse the photographs in this little stretch. They’re the best I could muster on my own.)

(Please excuse the photographs in this little stretch. They’re the best I could muster on my own.)

The real photographer was occupied otherwise at the time. She and Nasr had gone to visit Bedouin families.

Impossible to choose who had picked the better route, isn’t it?

Impossible to choose who had picked the better route, isn’t it?

But I was hurrying on then. I wanted to make the sunset from where Moses stood.

But I was hurrying on then. I wanted to make the sunset from where Moses stood.

And sometimes you’re just in places that take the photographs for you anyway.

And sometimes you’re just in places that take the photographs for you anyway.

And each of us – Debi and I – ended up where we were meant to be that day.

And each of us – Debi and I – ended up where we were meant to be that day.

Do you believe that -- that each of us is always where we’re meant to be?

Do you believe that -- that each of us is always where we’re meant to be?

There are no photographs for my descent at night. Actually, I got lost for a little while. But a Bedouin saw me and put me on the right path again.

There are no photographs for my descent at night. Actually, I got lost for a little while. But a Bedouin saw me and put me on the right path again.

Up by the summit, there are Bedouin huts that offer pilgrims tea and coffee by day. Most of those were closed up by now, but from within a few, firelight spilled out across the path, and soft voices rose in prayer and conversations.

And, oh, the stars.

I wish we could pour those stars into one another’s open hands right now.

Certainly, if there is any solitary journey, it must be this one, the Sikket Saydna Musa, where Moses walked alone to meet his God. The mountain had been cordoned off for Moses’ journey, and it had been decreed that anyone else who touched the mountain then must be killed.

Certainly, if there is any solitary journey, it must be this one, the Sikket Saydna Musa, where Moses walked alone to meet his God. The mountain had been cordoned off for Moses’ journey, and it had been decreed that anyone else who touched the mountain then must be killed.

What could be a more solitary way than this?

We had asked Nasr, “How many nights a month are you out in the mountains away from your family?”

We had asked Nasr, “How many nights a month are you out in the mountains away from your family?”

He thought awhile.

“Most nights,” he said.

But even this solitude is a kind of illusion, too,

But even this solitude is a kind of illusion, too,

…because actually Nasr rarely goes out into the mountains alone.

…because actually Nasr rarely goes out into the mountains alone.

“Bedouin like to talk,” he says.

“Bedouin like to talk,” he says.

After climbing the mountain, we told Nasr we wanted to go even deeper into the desert. We presumed we’d have to be driven from one place to another and make day-hikes from where we stayed.

After climbing the mountain, we told Nasr we wanted to go even deeper into the desert. We presumed we’d have to be driven from one place to another and make day-hikes from where we stayed.

“Why don’t we just walk the whole way instead?” he asked.

“But what about our travel-bags?”

“Schnapps can carry them,” Nasr said.

“Schnapps can carry them,” Nasr said.

But that’s a story for another day.

But that’s a story for another day.

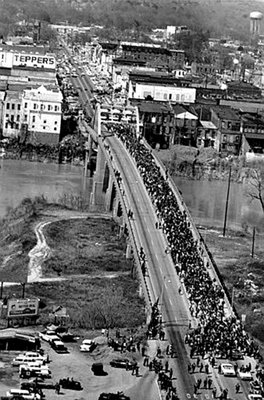

![]() Let’s go back to Moses’ journey one more time -- when the mountain was cordoned off to everyone but him.

Let’s go back to Moses’ journey one more time -- when the mountain was cordoned off to everyone but him.

Isn’t even this journey, which seems so absolute in its solitude, only a thread in a story bigger than any single life can ever be?

How big a story is Exodus after all?

How big a story is Exodus after all?

And how many people, for how many centuries, have seen their own lives writ large in it?

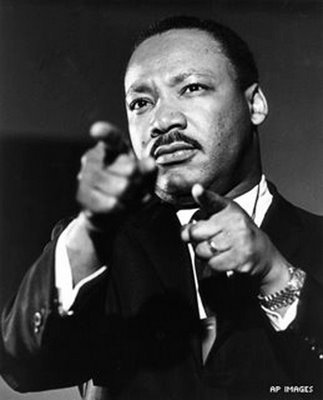

“I have been to the mountaintop,” he said. “And I’ve seen the Promised Land.”

“I have been to the mountaintop,” he said. “And I’ve seen the Promised Land.”

“I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people

“I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people

“…will get to the promised land.”

“…will get to the promised land.”

Because even this repentance-and-forgiveness path,

Because even this repentance-and-forgiveness path,

…this whole pilgrimage, in fact,

…this whole pilgrimage, in fact,

…even for the stretches we experience as a stony, narrow path,

…even for the stretches we experience as a stony, narrow path,

…it is not really a journey we are making on our own.

…it is not really a journey we are making on our own.

Notes

1. The title of this blog-post is stolen from the title of a beautiful article/reminiscence written by our friend, the Dingle peninsula artist Maria Simonds-Gooding (cf our March 21, 2009 blog-post) -- "On the God-Trodden Mountain" -- based on her own experiences at St. Catherine's.

2. And for a beautiful account of people finding their own stories within the frame of Exodus, you can listen here…

http://speakingoffaith.publicradio.org/programs/2009/exodus/

3. Our blog doesn’t discuss political and economic realities for Bedouin people. But we recommend an excellent story on the subject that was appearing in the March issue of National Geographic just when we were in the Sinai ourselves.

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/03/sinai/teague-text

Moses,

Moses,  Mt. Sinai,

Mt. Sinai,  Pilgrimage,

Pilgrimage,  St. Katherine's | in

St. Katherine's | in  Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage