Sometimes the world opens and takes you into secrets where it seems only you are meant to go.

But if we really notice—and if we really prepare ourselves, saying no to everything that has become irrelevant, and yes to the path that is ours and ours alone—then we find this opening happening more than we would have realized.

How many excuses we tell ourselves to avoid committing to who we really are—and to where the world would take us if we just had the courage to say yes enough.

A year ago we were in Aix-en-Provence,

…which means that during most of the daylight hours we were outside of it,

…sur le motif,

…walking in the footsteps

…where Cézanne had walked and painted.

We didn’t write about this then. And we almost didn’t write about it now. It means too much to us. And our words will fall short of how we really feel.

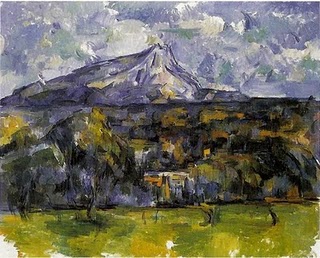

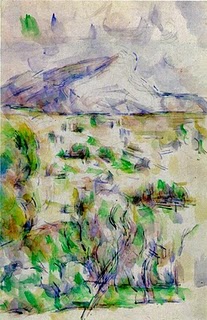

Another difficulty is with these images on your screen right now. They aren’t the paintings themselves, of course. So you can’t get the colors right. Or the genius of the touches of his brush upon the canvas.

Or the exact relationships among the colors and touches and empty spaces.

And yet if you click on these images, you begin to get a sense of them. (

Click here, for example, and move around awhile. Then backspace to return.)

What a thing it is to enter such a world again.

Now we only have what he had—our vision and our imagining.

And we aren’t meant to live in a surrogate world either.

It is the actuality of where we really are—together with our imagining—that creates anything real at all. And imagining, of course, isn’t the faculty of inventing something out of thin air, as if that were even possible.

It isn’t avoidance or dissipation.

It is the faculty of really seeing—in which our own true self emerges.

But you can’t say much about this, or you will frighten her away.

“Yes, that’s what I like to paint, the absent man, but totally integrated into the landscape,” Cézanne said.

It’s like that. You can’t see the absent man anywhere. And yet there isn’t anywhere he hasn’t been.

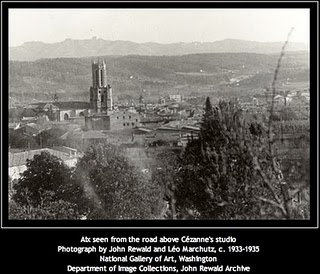

Cézanne spent most of his life in Aix. He was born and died there.

And so his life moved around the mountain, too.

And within the conformations of his native land, each small movement, each difference in the rhythm of where he walked and worked, taught him to see differently. And so it can teach us, too.

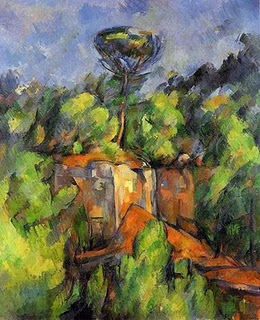

Later in his life, Cézanne rented this cabanon at Bibémus, where he could store canvases and materials, and sometimes take an afternoon nap, in between working sur le motif there.

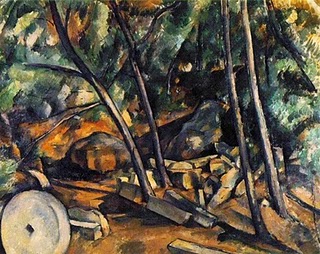

Bibémus was an abandoned quarry

…and afforded Cézanne mysterious angular man-made shapes in yellow ochre within the wildness that reclaimed the place.

He also later rented a room at the Chateau Noir along the Petit Rue du Tholonet.

As at Bibémus, Cézanne kept painting materials in the room to save himself the time and effort of transporting them to the places where he worked.

He wanted to buy the Chateau Noir, but his offer was refused. It would’ve brought him closer to the mountain, and he loved the wildness of the forest and grottoes there.

But sometimes the best thing that can happen is for our own plans to fall through.

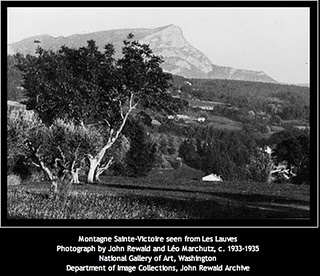

And so instead Cézanne built an atelier part way up the hill of Les Lauves, outside of Aix.

It must have been while the studio was still being built that Cézanne walked further up the hill of Les Lauves

…and came upon this vista of the mountain.

In his last two years, he would paint Le Mont Sainte-Victoire vu des Lauves many times, moving his easel a few feet one way or another.

The mountain always changes.

The mountain is always the same.

But you can see that in these late paintings there isn’t a way to the mountain any more.

You will have to integrate the experience differently now. You will have to compose it, too.

Aix has changed a lot since then.

Cézanne had shaken his walking stick in rage when electric street lamps first arrived in Aix.

So what would he think now?

And so in a world of such development, we hadn’t expected to be able to find the mountain any more. Of course, we knew that the geological formation would still be there—but certainly the solitude and presence would have fled.

Cézanne had said, “To see is to conserve—and to conserve is to compose.”

That simple-sounding sentence can ring so many ways.

Perhaps he wouldn’t have intended the sentence in an ecological sense per se.

But he saved the mountain anyway.

He didn’t move from art into political activism the way John Muir did.

Instead, he saved the mountain by seeing it.

Every place must have its poet, Wallace Stegner wrote.

That is, they must find each other.

And for that to happen, there must be a place—and within us, too—that can still be found

…and in which we can be found, too.

Wednesday, March 3, 2010 at 8:38PM

Wednesday, March 3, 2010 at 8:38PM  Artists,

Artists,  Cézanne,

Cézanne,  Mont Sainte-Victoire,

Mont Sainte-Victoire,  Pilgrimage | in

Pilgrimage | in  Pilgrimage

Pilgrimage

Reader Comments (9)

Sometimes I think the only real human enterprise is art. Taking that a step further: What painters do is mostly about looking and seeing. What writers do is mostly about listening and hearing. So, what this means is that the only real human enterprises are seeing and hearing. And I guess one needs to throw in touching, tasting, and smelling.

What a fine surprise on an early afternoon to unexpectedly find myself invited along on a stroll through Cezanne's world. Thank you.

I've been thinking something very similar—that there's something in the human spirit that *has to* compose or create as a way of fulfilling such seeing and hearing. And that otherwise, something feels very incomplete.

Beautiful.

I came for the giraffes and stumbled on this post shortly after and I really enjoyed a glimpse and experience into a moment of your trip again.

I liked the images & comparisons you make. The reflection of a year I'm sure also adds some good insight.

Thanks for sharing.

This was very enjoyable to read! And the paintings were wonderful. Thank you!

I was just at the Courtauld Instutite today for the Michelangelo exhibit there. Afterwards the exhibit,I found myself staring at the Cezanne paintings. I was staring at a painting of a forest with bold diagonal lines - and a sort of impossible copper sheen for the river. I've never seen so many shades of green and yellow. The textures. . .. What a shock when I found this blog! Many thanks again!

Paul Hamilton

I just read this beautiful post. "He saved the mountain by seeing it." That so perfectly describes these paintings that I love so much.

Paul, what a city you're exploring—and how well you're doing it. I'm looking forward to hearing how you put the whole experience into perspective. I've been reading about labyrinths lately, including how Troy became associated as a form of labyrinth (by nature of Aeneas' flight from it and subsequent journey)—and thus by extension "city" itself. When I read that, I thought of you and London.

And I know exactly what you mean about those greens and ochres and blues in Cezanne's paintings. I may know that forest painting you were looking at in the Courtauld. Someone has spoken of the "hundred thousand glances" that pass back and forth among the "touches" of Cezanne's colors. Be well, good friend,

Chris

I shouldn't known or guessed that you loved Cezanne, too, Georgiana. The south of France remains such a wonderful memory for Debi and myself—everything about the time. I can still remember conversations and ambling around the countryside just as spring was at its very beginning. Hope all's well and that we can see you soon.

Chris